The consequences of a no-deal departure are difficult to predict. The fate of the Irish border is still unclear. Hardly any sector of the British economy would emerge unscathed. But it is British universities and research which would suffer the most: hundreds of thousands of students, tens of thousands of researchers and academics, and hundreds of millions’ worth of subsidies are at stake.

The UK is a world leader in research and science. With under 1% of the world’s population, it produced over 15% of the most cited academic papers in 2017. British researchers are crucial partners in research projects across the world, and the country is an important contributor to the EU’s research budget. Yet this goes both ways – the UK hugely benefits from EU subsidies and grants.

UK research benefits from the EU – and vice versa

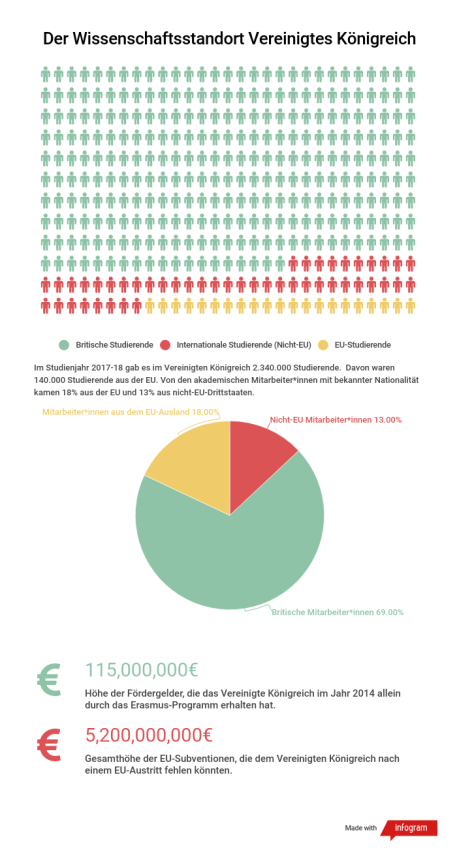

The UK’s academic scene is characterised by its international nature. Almost one third of those employed by British universities are foreigners, with many having taught and researched in the UK for years. This is particularly the case for EU nationals. UK universities also profit financially from the EU: exchange programs such as Erasmus or research programs of the likes of Horizon 2020 provide millions of pounds in funding every year.

Yet the European contribution to the success of teaching and research in the UK cannot be reduced simply to tuition fees and grants. No less important is the intellectual innovation brought to the table by international students – particularly those from the EU. This is also the case in the sciences, where cultural diversity is a valuable asset and the different perspectives it provides are particularly welcome, writes Peter Scott, Professor of Education at University College London.

The British scientific landscape is in danger

The precise consequences Brexit will have on higher education are difficult to estimate. What does seem obvious is that the attractiveness of the UK as a centre of learning and research will decline in the eyes of EU nationals. The lack of regulation provided by a withdrawal agreement would make entering the country more complex, funding research more difficult and studying more expensive.

From the year 2021 onwards, EU students would not be able to apply to UK universities through the program. It would become more difficult to take up British university credits or to undertake employment while attending university. Instead of paying ‘home fees’ (the same £9000 that British students also pay), EU nationals outside Erasmus would have to pay ‘overseas’ fees, which are significantly higher. It is likely that this would result in a fall in the number of EU applications to UK universities.

Stakeholders are, of course, aware of this: the Erasmus program blog reports that it is conscious of the insecurity posed by the threat of a no-deal Brexit, and that solutions for such a scenario are being sought. What remains unclear is what those solutions may look like.

This insecurity also affects EU citizens who research and teach in British universities. According to the German Academic Exchange Service, their feeling of being welcome in the UK has declined significantly, while xenophobic incidents have increased. In some cases, this has already resulted in deferred employment contracts. It is very likely that, in the coming years, the UK will suffer a ‘brain drain’. There are no specific figures yet, but programs such as the ‘Humboldt Professorships’ have reported an increase in applications from academics in the UK – highlighting a rise in the number of people who wish to return to the EU. This is a heavy loss for the UK’s higher education sector.

When approached by the team of our German sister edition Treffpunkt Europa, Professor Peter Scott confirms the damage Brexit will inflict on British universities:

‘Brexit will be a triple blow to the UK’s universities. First, opinion among academics and students is overwhelmingly pro-remain, so universities are being taken out of the EU against their will. Second, UK institutions will lose access to European funding programs, particularly for research. This is a tragedy because they had been enthusiastic, and successful, participants in these programs. Finally, as a result of Brexit, the UK will be labelled a ‘nasty’ country, which has turned in on itself and espoused nationalist, and even xenophobic, values rather than internationalist and cosmopolitan ones. Another tragedy in the light of Britain’s long history of liberalism and democracy.’

The financial restrictions, the uncertain legal status, the brain drain and the growing xenophobia – all of the above will contribute to a loss in competitiveness for the UK’s scientific landscape – with potentially catastrophic consequences for Europe’s research sector.

Follow the comments: |

|