Four decades later, the parliament still lacks some basic powers, and elections are still fragmented and dominated by horse trading. If one believes the national governments, it has to be this way to prevent a monstrous superstate. But that’s getting everything backwards.

The “superstate” hoax

Looking closely, national governments and their parliamentary majorities have transferred legislative powers from their national parliament not just to the EU, but also less democratic supranational organisations, mostly to create areas with common rules, to support their nation’s prosperity.

That wouldn’t be bad by itself – but giving away powers to the EU and later attacking reforms that would take those powers from the executive and return them to a democratic parliament is fundamentally dishonest.

Follow principles, reclaim influence

Every now and then politicians propose changes in how the EU reaches its decisions – essentially, everyone complains about how the EU institutions are stacked against them. The larger states like Germany think the EP is unfair since small states are overrepresented, while the smaller ones dislike the EU Council which is dominated by the large states after the Lisbon Treaty. But proposals just attempting to raise the weight of one’s own state in the institutions are doomed to fail.

The better approach would be an international one, with the current order dominated by horse trading – which only makes everyone feel unfairly treated – giving way to one derived from principles aiming to treat people and states fairly. Depending on which principles one deems centrally important, people can get different proposals as their result. But that only means that one has to discuss the pros and cons of each of them, which is still better than blindly continuing the current undemocratic path.

Parliament and Council – a new balance

Large, small and mid-sized member states all seek a fair share of power by which they won’t be simply outvoted. This can’t be reached by changing just a single element – but readjusting the institutions based on already existing proposals could achieve a new balance.

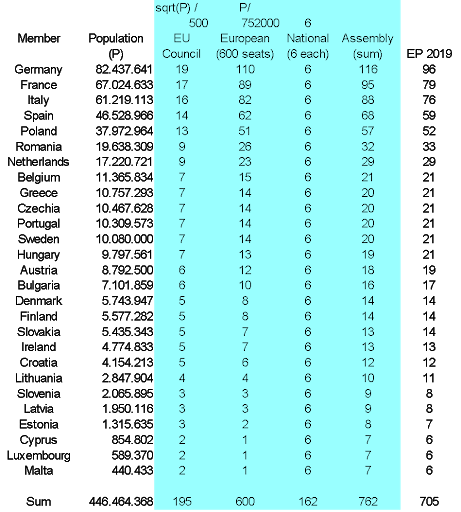

The Cambridge Compromise is the basis of my proposed division of the European Parliament into two chambers: A lower house with 600 members, elected by all EU citizens equally, with the same voting law and an upper house with 6 members per member state, elected by the citizens of that state (using personalised Proportional Representation or Single Transferable Vote) with a national voting law (this addresses the fear of citizens of those states, fearing to lose all their influence)

The Commission would be elected by members of both chambers, while legislation would need a majority in each chamber. With both chambers involved in legislation from the beginning, complaints coming from small and large states will all have to be addressed by legislation to be successful.

This will lead to an increase of EP members from large states. In return, the Lisbon change in the EU Council should be reversed and replaced by the Jagiellonian Compromise. This change was a huge deviation from previous rules, and was heavily pushed by the larger member states. After Brexit, Germany and France will have more than a third of the EU population, which means they can reach the blocking minority (4 states with 35% of people) with the help of almost any two other states.

But the German-French “tandem“, being such a one-sided approach, just ended up so unpopular that Germany and France gained some veto power but lost cooperation – and the gridlock will eventually cost every state in the EU dearly. It would be wiser to return to balance with the Jagiellonian Compromise.

Legislation involving all parliaments

The current legislation in the EU is started by the European Commission, while the parliament itself has no initiative power. This arrangement is an artifact from earlier times that has outlived its usefulness – originally, the Council was the main legislative body, and the Commission was given initiative power since it was trusted to treat all states fairly while the Council was feared to create proposals only useful for their supporters.

This clearly is no longer the case. Meanwhile, a directly elected European Parliament has existed for almost 40 years, with its members sitting in international groups, leading to proposals caring for all of the EU – which unfortunately have no legal meaning – while the Commission treats smaller states more harshly for not following regulations than what it does with the larger ones.

It would be better for legislation to involve all actors from the beginning. A proposal might come from the Commission, but also from a large enough group of MEPs, or from the Council, or from a petition by one national parliament to start legislation, supported by others. If the Parliament decides to work on the proposal in a committee, national parliaments would have access to the proposal and could give input while it is still being fleshed out. This would prevent far-reaching proposals from slipping under the radar, only getting to be known when the legislative process is almost finished.

A mediating EU President, an unthreatening Commission

The EU doesn’t need a President who is strong and intimidating to the member states, it just needs to be effective. It can gain cooperation by having a President whose role it is to find common ground between the member states and the institutions, continuing the role of the current Council President.

After an EP election, the President would first hear proposals from Council and Parliament on who should be in the Commission, and would then make a proposal to the Parliament. The Parliament would either vote for the Commission outlined in the proposal, or vote against it and then vote for another Commission.

This Commission would not have one powerful President, but instead 9 Federal Councillors responsible for different subjects, and more Assistant Councillors working in subfields of these subjects. (The current Commission already has several Vice Presidents, so the reorganisation wouldn’t need to be from scratch)

After the Parliament elected a Commission, the Council could veto it or its central members (I think two: one would be foreign and security policy, another finance and currency – and if the EU level gets more powers transferred to it, there would be three, splitting the foreign policy part from the defense part). This way, the order of who gets to choose and who only gets the up-or-down vote is switched. If the Council wanted a specific person elected to the Commission, they’d have to approach the Parliament and President beforehand, and be willing to compromise.

As for the Spitzenkandidat – I think there should be several people from each party vocal for their respective political field, and the media be holding debates on these. In the end, the Parliament will vote in a Commission with members of different groups, instead of one Spitzenkandidat whose group might not get much more than a quarter of seats.

Democracy is not an afterthought

These days, too much of European policy proposals are dominated by national states’ interests and horse trading, while democratic structures and decision making are neglected. But democracy can’t be relegated to times when all other problems have been solved (as there are no such times). Democracy is not an afterthought. And if it’s treated as such, don’t wonder why it disappears.

Follow the comments: |

|