Ukraine Year One - Davide Cinotti, Eurobull

It is November 2013. The Russian president, Vladimir Putin, convinces neighbor Viktor Yanukovych – Ukrainian Head of State – to retire from a commercial agreement with the European Union. In the Eastern European country, the Euromaidan explodes. At first, hundreds of thousands of people, then a million, flooded the streets of their country to protest against the decision of Yanukovych.

After days of protests and violence from both parties, Yanukovych escaped and the government fell down. In Crimea, Russia counter-acted. First, local protesters and then “green men, soldiers without insignia, took control of the entire area. Then, on the 16th of March a referendum- contested by the UN – consigns the peninsula to the Russian Federation. It becomes an international crisis.

Some years later, with the excuse of bilateral military exercises, Russian forces started to deploy troops on the Ukrainian-Belarusian border. From October 2021 to February 2022 their deployment intensified up to the border with Crimea. After this demonstration of power, Russia proposed two deals to NATO, which included some “security guarantees”, as the exclusion of Ukraine from any possible adhesion to NATO itself and the gradual reduction of NATO military presence in Eastern Europe. It also expressed its intention to react with a military response to what it described as an aggressive line from the Atlantic Alliance.

Since the start of the conflict on the 24th of February of 2022, there are still no visible signs of peace. Instead, the consequences are pretty clear. From a humanitarian perspective, the war has turned millions of people into refugees, thousands are dead and many cities left under siege. Economically and politically, the Russian invasion has generated a shockwave which hits the markets and the neighboring countries – but it is not only about this. Despite the contradictory versions of the situation of the two nations, ISPI has estimated a realistic number of deaths at 100.000 in the first 10 months of the war.

In the XXI century, it seems absurd to see two countries battling in Europe, without rules and any truce, for ideas that can be tagged as old and ethno-nationalistic such as “national integrity” and “auto-determination of the people”, now probably outdated in our value system.

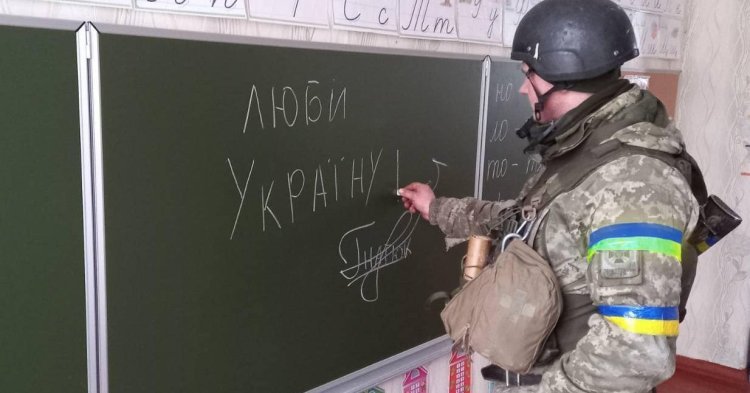

From the Russian side, many thought that the sanctions would have led to the fall of the Kremlin’s power. With the exception of some confusion in the main cities, there was no sign of a widely diffused protest. It has been years now that we are observing in Iran or Russia, a regime change provoked by the Western economic sanctions. Many Russians are still strongly nationalist and believe in the messages coming from Moscow: it is a campaign alternating words such as “special operation” and “de-russification”. The latter is a reality in Ukraine since it is shared by the population and the intellectuals. In the last year, many squares and streets named after Russian public figures were changed, as well as monuments dedicated to Russian musicians, scientists and politicians. The Russian language was also dropped from official communication channels.

Despite the idea, in the first years of our new millennium, that we were entering a new reality of the war, recent history taught us the opposite: nationalist parties are stronger than ever as shown in Latin American and Western countries.

Even war didn’t change at all. Mainstream channels and the independent ones as well show us a war fought inch by inch – not differently from one of the battles of the First World War in Isonzo, Italy. One year after the war began, Russia is preparing a new deadly offensive. After one year and 100.000 deaths, we are again at the starting point.

It was not so short - Jacopo Barbati, The New Federalist

One year ago, when Russia finally invaded Ukraine, the majority of European public opinion really did not expect it. And much like COVID was unexpected, the media reacted in the same way: the topic was all over the news for days and “war experts” were frequently interviewed or consulted.

Several of them stated that Russia’s intentions were focused on obtaining a surrender act from Ukraine in 24-48 hours, that Zelenskyy and other top officials of the Ukrainian government would be arrested or killed, that if the war would have gone on longer than expected, the Russians could have even used tactical nuclear bombs - but it was not the case for all of these assumptions, and beyond.

And this is a relief, in a sense: Russia has not won the war, Ukraine is still an independent country even if wounded and invaded. But, of course, more than a relief, this is still a tragedy: thousands of people died or lost everything.

What has this one year taught us? First of all, that this war won’t be short - as all wars. And then, that we, as European public opinion, are so polarized that taking decisions is becoming an extreme sport. We could - unfortunately - already experience it during the pandemic but we had the ultimate proof in this last year.

Although there was clearly an invader and an invaded, for some in Europe it was difficult to not blame the invaded. “Ukraine provoked Russia by having relationships with the EU and NATO”, “The war would end now if Ukraine would surrender”, “If we give military support to Ukraine there will be more deaths”, “We cannot host all the Ukrainian refugees”.

Therefore, giving military support to Ukraine was a lot harder than it should have been, even if it has been done in the end. Yes, it is true that this is making the war last longer, but the alternative would be an annihilation of Ukraine and a validation of the Russian invasion. Invasions are never legitimate, but unfortunately this seems to not be the mindset of the Russian government at the moment.

Recently, the Russian government is intensifying attacks towards the Moldovan one, accused of “anti-Russian behavior”. As the easternmost region of Moldova, Transnistria (or formally Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic), is a self-declared Republic not officially recognized as such by Russia but with heavy Russian support, even under the military point of view (the Council of Europe deliberated to designate the region as a “Russian occupied territory”), the risk of Russians military actions in foreign, sovereign territories beyond Ukraine is not remote or impossible.

As all wars, this one should simply not have started; but since it has, it should be faced and not avoided. A war in Ukraine is a war in Europe, and the sooner Europeans will fully understand it, the better.

Ukrainians and their resistance - Sven-Alexander Gal, România Europeană

The history of Ukraine is a tumultuous one. Today’s territory of Ukraine has witnessed many historical events. The Ukrainian national state of today draws its juice from Kievan Rus’, but also from Zaporozhian Sich led by the hetman Khmelnitskyi, a territory very close to the medieval Romanian states, mentioned by the Moldavian chroniclers of the time. Also, on the territory of today’s Ukraine we had the border between the Russian Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which during the First World War made this area a line of the Eastern Front. After the First World War, two Ukrainian states were founded: the Ukrainian Republic, which included Ukrainian territories in the former Tsarist Empire, and the Ukrainian People’s Republic, which included territories from Austria-Hungary. These states did not resist due to unrest in those territories, Kyiv being occupied for a period of one year by no less than 5 state entities. In the end, a large part of Ukraine became part of the USSR, and the bloodiest episodes of modern European history took place on the territory of today’s Ukraine: the Holodomor imposed by Stalin and the Holocaust, modern-day Ukraine being the territory with the most victims of the Holocaust.

Ukraine declared its independence in 1991, and the country’s post-independence history is the most tumultuous history of a post-Cold War former communist country.

Until 2004, the state was strongly controlled by former communist dignitaries and former KGB agents. In 2004, the Orange Revolution took place, after which Viktor Yushchenko became the president of a Ukraine that looked towards the West. The economic crisis hit Ukraine hard, and in 2010, the pro-Russian parties through Viktor Yanukovich took advantage and imposed themselves electorally. This whole period lasted about 3 years. In 2013, the protests started caused by Viktor Yanukovych’s decision not to sign the Eastern Partnership, an antechamber for defection to the EU. For 3 months, Ukraine was gripped by protests, and in February 2014, the Yanukovich Regime was finally defeated. What followed, we already know too well. Russia annexes Crimea and is waging a hybrid war in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

The West behaved towards Russia almost as if nothing had happened, and this naivety has a cost.

On February 24, 2022, after long propaganda activities, Vladimir Putin decided to initiate the full-scale invasion.

That morning will always be in my personal memory. I will forever remember how I was heralded of the news by my father. At that moment, I froze: it seemed like I was living in a parallel world. It seemed that hell had poured out on us.

I watched the news all day. Romania was also gripped by despair. They were talking about the fall of Kyiv and how Moldova and then Romania are going to be invaded by the ‘great bear’.

In those days, the Romanian-Ukrainian borders were stormed by refugees on one side and on the other, by warm-hearted volunteers. The organization in Romania regarding refugees was exemplary in those days.

However, after a few months with all the implications that this war had for Romania, this topic ended up having a secondary role in the country’s press, inflation hitting the Romanian economy hard. However, the good part is that the Romanians have maintained their level of pro-Europeanism and pro-Atlanticism from a year ago and politicians who are known to be promoting Russia are strongly marginalized by Romanian society.

However, moments like the recapture of Kherson caused a wave of enthusiasm for us as well. Romanians do not forget the difficult years of the communist regime of Soviet origin and they do not allow themselves to be so easily manipulated by Kremlin propaganda. However, Romania’s government could have been more proactive, as was Poland’s, which played its role well as a regional leader this year.

Follow the comments: |

|