The early rise to power of finnish eurosceptics

Early on, finnish eurosceptism reached high levels of power. For us, it came in the 2011 parliamentary elections in the form of the Finns Party. The party, led for 20 years by one of its founding fathers Timo Soini, got an astonishing 19.05 per cent of the votes casted, and became the third largest party in parliament. Before the 2011 elections, the highest support the party had ever recorded was 4.05, which came only four years earlier.

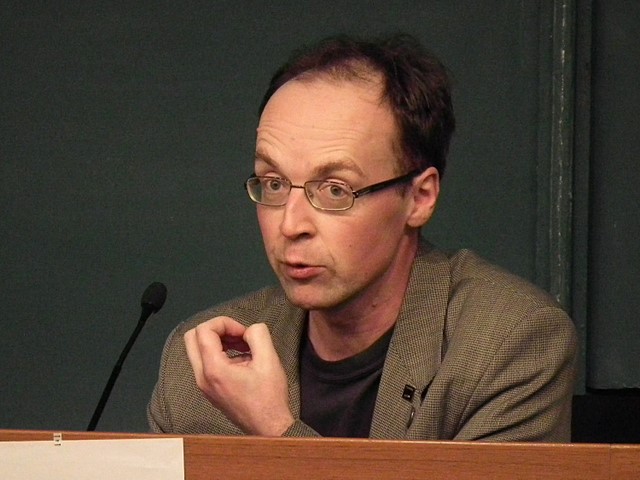

Timo Soini, founder of the populist Fins Party

The result shook Finnish politics to its core. Soini became the leader of the opposition, and the government had to be formed by the election winning center-right National Coalition Party on a basis of a six party coalition in a parliament consisting of eight parties. The coalition, led by the center-right, had one of the broadest ideological ranges ever for Finnish politics: former communists, ecogreens, christian-conservatives and extreme fiscal hawks working towards a commonly agreed platform. As one can imagine, it wasn’t a smooth ride, and the mid-term departure of prime minister Jyrki Katainen for a post at the European Commission certainly didn’t make it any easier.

Timo Soini speaks to the press

The four year term ended in disarray, with the leaders of the National Coalition and the second largest Social Democratic Party turning on each other, and refusing to work together regardless of the election result.

The Finns Party success at the 2015 elections

The 2015 elections were another victory for the Finns Party. The former second largest opposition party, centrist and agrarian Centre Party, won the elections and the right to form a government. The Finns followed suit with a 17.65 per cent share of the vote and only one parliamentarian less than four years before. In those four years, the Finns Party gained ground in both the local, European and presidential elections, and Soini pushed out the biggests racists from the parliamentary group. The party had established itself, built an organisation and recruited operative talent to its payroll.

Petteri Orpo (left), Finance Minister and Leader of the National Coalition party, Juha Sipilä (centre) Prime Minister and Center Party leader, and Timo Soini (right)

This time the government was formed on a basis of the Center Party, the third largest National Coalition, and to the surprise of some, the Finns Party. For the first time in the history of modern Europe, a eurosceptic, nationalist and populist party was given a pass to the government. Soini himself took the post of a Foreign Minister (insted of Finance Minister, normally allocated to the second largest party in coalition), and the party now also controls the ministries of Defence, Social Affairs and Health, and Justice.

Why finnish populism is different

Outside of Finland, I’ve found, this has been considered astonishing. How can one form a coalition with a party like the National Front or the Sweden Democrats?

The answer is that one probably couldn’t. The Finns party isn’t like the National Front or Sweden Democrats, even though the international media has repeatedly compared them to other Nordic populist parties and nationalist and right-wing movements around Europe.

The Finns Party isn’t like the National Front or Sweden Democrats...The party’s core ideology comes from its predecessor, the Finnish Rural Party, not from the pan-European anti-immigration movement, combining left-wing economic policies with conservative social values.

It’s true that the Finns Party shares with them the same euroscepticism and critical approach to globalism, and the party has risen to power with empty promises and dangerous statements. At the same time, the Finns Party combines left-wing economic policies with conservative social values. The party’s core ideology (at least the core ideology of Soini and the rest of the party’s ruling faction) comes from its predecessor, the Finnish Rural Party, not from the pan-European anti-immigration movement. In the European parliament, the Finns Party is a member of the Conservatives and Reformists Group, not the radical right.

The Finns Party in power: toning down and falling popularity ?

Upon taking government office, the party had to change its rhetoric. A small nation like Finland simply can’t afford provocative statements by its Foreign Minister, and the biggest loudmouths of the party were silenced and pushed to the backbenches due to demands from the other coalition parties. Though the critiques have quite legitimately held Soini responsible for not condemning the racist voices rising from within the parliamentary group (at least with the severity they’d deserve), all four ministers of the Finns Party are from its moderate wing, and the anti-immigration racists have been kept out of the center of power. All in all, the government has been able to keep a relatively sane approach towards immigration, economic and foreign policy.

Since taking office, the support for the Finns Party has plummeted. According to the latest poll by the National Broadcaster Yle, the party now enjoys the support of only 8.4 per cent of the voters. According to Yle, many former Finns Party adherents think the party has betrayed the working class by signing off on the government’s cuts to wages, benefits and services. One possible explanation could also be the switch in rhetoric the party had to sign up to, and perhaps the biggest challenge has been the combination of it all. Like all three parties in the government, the Finns have suffered from the unpopular third Greek bailout, the refugee crisis, and the faltering economy.

Whatever the exact reason may be, giving the Finns Party power has stripped them from popular support. However, the strategy widely admired by some will face its biggest test in June, when the Finns Party will choose their next leader.

A leadership race divided between moderate populist and anti-immigrantion factions

After leading the Finns Party for 20 years, Timo Soini announced last Sunday that he will not be seeking another term as the party’s chairman. The decision came as a surprise to many, but the kick-off to a leadership race was fast.

The Finns Party is deeply divided into two factions: the moderate populists and the anti-immigration extreme-right-wing. The leadership race is expected to be a tight battle between these two.

Sampo Terho (left), former MEP and close supporter of Soini

The moderate populists are gathering behind the leader of the party’s parliamentary group, Sampo Terho, who announced his candidacy last week. He’s a former member of the European parliament and close supporter of Soini. It was all but obvious that Soini and the party elite had carefully planned the announcement, and the overwhelming statements of support that followed, to give Terho an early lead in the race. He himself tapped into the party’s anti-immigration base with statements meant to drive out right-wing competition. “I think it is a central tenet of immigration policy for Finland to remove all the factors that attract asylum seekers to Finland,” he declared at a press conference according to Yle.

Like Terho, two other parliamentarians have announced their candidacy, but their chances of winning are slim.

Terho’s toughest contestant, MEP Jussi Halla-aho, declared his candidacy on Monday. Halla-aho is the leading figure of the party’s anti-immigration wing and received the second largest amount of personal votes in the last European elections, and over twice as many as Terho. He is a hard-right nationalist with a history of racism. In 2012, he was found guilty of ethnic agitation and disturbing religious peace by the Finnish Supreme Court, after he had posted racist and anti-Islamic texts on his popular blog.

Halla-aho’s candidacy means that in the Finns Party convention in June, the whole Finnish approach to dealing with populism is put to test. If Terho wins, it’s likely that the Finns Party will stay in government, their support will stay at the levels of a Finnish mid-sized party, and the rapid rise of populism has been tamed. If Halla-aho wins, the government will immediately collapse, new elections will likely follow, and no one really knows where it all will lead.

Jussi Hallo-Aho MEP, a tough contender for Sampo Terho

The worst case scenario is that Halla-aho, an outsider from Brussels carrying no baggage from the current difficulties in government, will be able to regain the party’s support and pivot its platform to extreme-right. This would mean that instead of the centrist eurosceptic populists, the Finnish politics would be haunted by an ultra-nationalist anti-immigration party with both popular support and government experience.

The Finnish conclusion : even moderate populists can’t be trusted with power ? To be confirmed in June elections

Right now it seems unlikely Halla-aho would win. Soini, an obvious supporter of Terho, has crafted the party from scratch and knows every little detail of it. There’s a saying that “In the Finns Party, Timo Soini always wins”. Halla-aho on the other hand is a popular but uncharismatic politician with a Ph.D., who prefers staying out of the spotlight.

However, when it comes to dealing with populism, the main lesson from Finland is not all that clear.

The notion that “the best way to deal with populism is giving them power”, can’t yet be supported by our experiences. At the same time it’s good to remember : the Finnish people didn’t give power to the National Front or Northern League, but to a populist party with a unique and fairly moderate character.

So what are the lessons from Finland in taming populism? The reality is that no one knows yet, but you might want to wait until July before you copy our approach.

The writer is the International Officer of JEF-Finland and works as a Managing Director at a small center-right think tank affiliated with the National Coalition Party of Finland.

Follow the comments: |

|