Comparing broad Glaswegian, Aussie drawl and Canadian lilt shows us the incredible diversity and geographical spread of our language, arguably the most useful mother tongue on the planet. The Anglophone phenomenon comes with its own bear traps. 61% of British people can’t speak a single other language. We thus receive the dubious award for the most monolingual country in Europe.

There is something very British about the way we consistently overestimate the importance of our own language (only 38% of EU citizens outside the UK and Ireland know enough English to have a conversation, and 6 of the world’s 7.5 billion people speak no English at all) and find excuses not to learn anyone else’s. We have an unfortunate tendency to reduce language to its functional value of bare bones communication; if person A from country B learns our word for C, we’re good. We persistently neglect that language is also intrinsically tied up with culture, identity and personality.

“A different language is a different vision of life”, quipped Italian film director Federico Fellini. Speaking only the language handed down to us by our parents means we miss a whole dimension of the human experience and the pleasure of authentically discovering another layer of the cultural richness of our world.

It’s one of the reasons the Erasmus scheme is such a wonderful project. Improved language skills, for me, come a distant third behind cultural understanding and international friendships in terms of the benefits of the scheme. When I came back from my year in Lyon (with a terrible suntan, several extra kilos, and reluctance), I had learnt the words for bottle-opener, ski lift and puncture. Without meaning to, I had also had a glimpse beyond the stereotypes of wine and shrugging; a glimpse of the differences in attitude to the work-life balance, perception of the role of the state, and emphasis on enjoying today rather than anticipating tomorrow. These deep cultural differences are linked to and expressed in the structure, vocabulary, idioms and intonation of the language, and are untranslatable.

Is a lack of motivation the only factor holding us back? Enticed by the offer of a cheese and wine evening, as well as speaking a little of the language I miss hearing all around me, I recently headed along to a French society event at my university and got chatting to an English lit student, who was stupefied that I could converse with the few French students present. “I’d so love to be able to speak French!” she said enthusiastically. Someone mentioned that there were free classes at the university that she could take as an optional module. “I know, but I’d get such bad marks, it would bring my average right down.”

It was my turn to be stupefied. In university environments where classes of all levels are so often offered for free, it is the fear of failure which is a deterrent. I don’t by any stretch claim to have perfectly mastered the languages I’ve tried to learn, but among Brits, I have noticed this curious conviction that acquiring a conversational level in a foreign language is simply not possible, or else so difficult that the chance of success is a dim, scarcely visible glimmer on the horizon. Fluency is like a magic trick, an appealing result after a mystifying process. It’s true that scrambling around for an impossible-seeming pronunciation or a but-I-only-learnt-it-yesterday conjugation requires a willingness to be vulnerable. Sticking to good old English (probably raising our voice, just to make sure we’re understood) shields us from failure but also from the thrill of occasionally, eventually, getting it right. Sticking to good old English also makes it much harder to recognise the effort made when someone learns to speak it, and more fundamentally, to learn to communicate across cultures and put ourselves in others’ shoes.

Monolingualism is also an outward sign of our delusion of exaggerated national greatness and reinforces a feeling that the world should come to us. Speaking our own language wherever we go and expecting others to learn it gives us the upper hand and only adds to our very British superiority complex.

Nowhere is this complex better represented than the Brexit debate. “Believe in Britain! The EU will come crawling!” was the main “argument” shouted at me while I was, undoubtedly very annoyingly, shoving leaflets into hands in York city centre last weekend. The claim hardly speaks of a humble acknowledgement of cultural tolerance, understanding and mutual respect. I’m not aware of any statistics linking language learning to the Remain vote, but I would bet my degree on the correlation being a strong one.

At a French conversation evening I drifted along to at a pub in town, the inevitable topic surfaced; but, as if to avoid swearing, the term “the B word” was employed. The ironic phrasing might have produced a few minimal, rueful smiles of acknowledgement (it made me think of He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named in Harry Potter), but it was enough to provoke a minute of awkward, stony silence. Then someone changed the subject, and with relief everyone moved on. I looked around the table of people grappling with various levels of French, some more, some less advanced than my own, and felt no doubt that they had all voted “Remain”.

Had these people learnt French because they were searching for this “different vision of life”, or at least seeking to understand a foreign culture? Or did the process of engaging in language learning help them become more open to the world? It’s a mutually reinforcing spiral; learning a language pushes us to build relationships with people who speak that language, outside of our own borders; at the same time, mastering a foreign language facilitates and fosters these relationships. I truly believe that, were more of us to be willing to shoulder the vulnerability of learning a foreign language, increased cultural awareness would have stemmed the flow of Britain’s turbulent history of Euroscepticism. I am saddened by the idea that, should Brexit finally occur, there will be even less interest in language learning – fewer visions of life, fewer international friends, less cross-cultural understanding – and that people will more than ever be more focussed on, and limited to, our monolingual island.

The usefulness of being a native English speaker is undeniable; being able to (probably) get by in our first language in Vienna, Venice and Vilnius is pretty great. But we should recognise that this is a privilege that leads us to put on linguistic and cultural blinkers. Without these, we might feel closer to our European neighbours, in spite of the ocean between us.

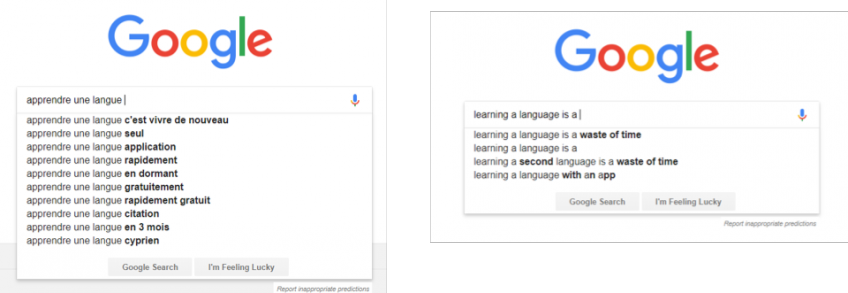

P.S. As a side note: while researching the original of the quote on different visions of life for both the English and French versions of this blog, I came across an interesting difference in search results:

Follow the comments: |

|