Flavia Sandu from Romania

Romania was the only Eastern Bloc country whose citizens overthrew the communist regime violently.

My mother was 16 years old in 1989. It was during the winter vacation that the events of the Revolution unfolded. The town she lived in did not have any violent incidents as such, but Bucharest, where much of the action occurred, was less than two hours away. My mother used to love historical movies, or at least the few they were allowed to watch. For her, it felt incredibly surreal to see shootings, people dying and barricades burning on the news and not on a film. She couldn’t believe the Revolution was actually happening.

The first thing she thought of was that, if communism were to fall, she wouldn’t have to take political economy classes in school anymore! They had an eccentric teacher who spent most of the teaching time quoting Ceauşescu’s speeches from the Romanian Communist Party’s Congresses. Then she realised she would be able to speak freely, not just at home, but everywhere, without being afraid. She spent many long nights where sleep was impossible. She kept watching the reports because she wanted to know what was going on all the time. Non-stop TV was a new thing anyway, as until then they had only had one or two hours per day.

Many people used to dream of eating foreign chocolate or exotic fruits which were a rarity during communism. It wasn’t the case for my mother. She said they were lucky in that regard, as my grandpa used to have some connections and managed to get some of those things underhand sometimes. Instead, my mother wanted to have access to information, and, most of all, to travel.

It’s strange to think that, this November, Romania is going to the polls to choose its president for the eighth time since the fall of communism.

Madelaine Pitt from the United Kingdom

My parents got married in the summer of 1989. It was a year which, for Britain, shared important similarities with the current day. Then and now, we have seen drastic changes over a decade of increasingly right-wing Conservative rule. By 1989, former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s era of power was coming to an end. Trade unions had buckled, public services had been privatised and manufacturing neglected. While the financial City of London was starting to boom after aggressive deregulation, poverty and inequality had increased in a deeply divided society. Today, after years of austerity, Britain is again bitterly divided – most notably over its membership of the European Union.

Although Thatcher supported the idea of eastward European enlargement even before the end of communism, the seeds of British Euroscepticism were well nourished by her discourse on Europe. Nowhere can this be better observed than in Thatcher’s reaction to the fall of the Berlin Wall. While my parents remember that the accelerating erosion of the Iron Curtain was greeted with hope and optimism for a peaceful future by the British people, this attitude was not echoed by our political leaders. Former Chancellor of Western Germany Helmut Kohl reported that, at a meeting of European leaders, Thatcher had stated that Britain had “beaten the Germans twice, and now they’re back”.

This is very telling of the Conservative Party’s inability to see our European neighbours as partners and friends, and their insistence on seeing them as competitors, or even enemies. Thatcher was better known for cosying up to fellow free-marketeer across the Atlantic Ronald Reagan than for seeking to build a strong European family; how painful it is to see Boris Johnson pandering to Donald Trump while holding the EU in contempt. Thatcher’s statement also reflects the Conservative Party’s jealousy over Germany’s economic success and, more broadly, an insecurity complex about being a declining power in Europe and the world. Thirty years on, the debate surrounding Brexit shows that little has changed.

Marie Menke from Germany

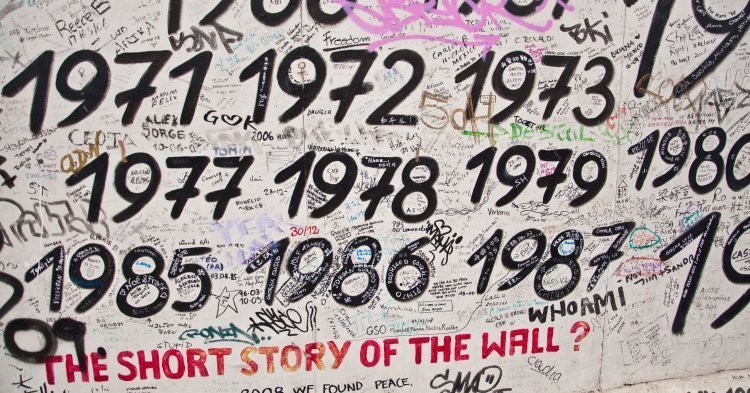

What happened in 1989 changed Germany on both sides of the former border too profoundly for words. Between 11.30pm on November 9th and a quarter past midnight on November 10th, about 20 000 citizens from East Germany crossed the border to West Berlin. An official from the Socialist Unity Party of former East Germany or the “German Democratic Republic” (GDR) accidentally declared that new travel regulations have come immediately into effect. The wall that had divided the city for 28 years and 88 days had fallen.

Some of those who crossed that night and in the weeks and years to come had desired reunification. Some had previously taken to the streets to fight for democracy, some had even fled the country. Others were in favour of further solutions, among them the continued existence of two separate German states. For some, East Germany was struggling too much to survive any longer. For others, the fall of the Berlin wall came entirely unexpected. The narratives vary significantly.

Today, significantly more East Germans believe that West Germany benefited from reunification, whereas significantly more West Germans believe that East Germany benefited from reunification. Having grown up in West Germany, I spent more time in school learning about ancient Rome than about the GDR. Divisions do not solely exist on maps; they exist in our minds. The statistics depict a country which is in many aspects unequal; ever since what Germans call the „Wende“, which can be literally translated as „turning point“, salaries have been higher in West Germany while unemployment has been higher in East Germany. On top of that, though, both the numbers as well as countless personal experiences tell the story of a country which has not yet fully got to know itself.

Jan Sztanka-Tóth from Hungary

The transition in Hungary from communism to democracy, when compared to that of other countries, was peaceful rather than tumultuous. That is not to say that there were no protests or political activism in Hungary in 1989; for example the reburial of Imre Nagy, the Hungarian prime minister who led the country during the 1956 ultimately unsuccessful revolution against the communist regime, was attended by a few hundred thousand people. However, communist Hungary was dubbed “the happiest barrack of the Soviet block”, or “Gulyáskomunizmus”, which is a combination of the word “Gulyás” being a traditional soup rich in meat and “communism”. Due to economic reforms introduced in the 1960s, life in Hungary was not as bad as in the rest of the neighbouring states, which ultimately resulted in less motivation for change when the time came in 1989.

Nevertheless, opposition activism amongst students and the elites leading up to 1989 grew. When the communist regime came under pressure from domestic activism, and changes on the global stage, it decided to give in, thus letting the pro-democratic opposition step in. The communist party was dismantled in 1989, but its moderate wing consisting of communists who had been calling for changes during the previous years went on to form a reformed party. In 1990, the first democratic elections in 43 years were held and a government was formed from pro-democracy parties.

This gradual change of power haunts the political landscape in Hungary to this day. The current ruling party Fidesz has long argued that, since there were only amendments rather than major changes to the constitution in 1990, the transition was not a “true” change. At first glance, it is hard to disagree; however, it was exactly this argument that led to a rewriting of the Hungarian constitution in 2011. This is the basis of Orbán’s “illiberal democracy” today.

Basile Desvignes from France

On 10th November 1989, while at a conference on Europe in Copenhagen, the President of France François Mitterrand expressed his joy over the fall of the wall: “This is a happy event that marks progress for freedom in Europe”. Throughout the night, French radio followed the unfolding events which we know now would change the course of history. Over the following days, images of jubilant crowds were broadcast on television, and the French were fascinated by the story.

Today, a quick scan of the articles about the thirtieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall allows us to measure how the image of Europe as depicted in the French press have changed since 1989. “Gloomy anniversary”, “heavy atmosphere”: most of the articles in French newspapers concentrate on the persistence of social, economic and cultural inequality between eastern and western Germany.

The anniversary of the fall of the Wall is also an opportunity to evaluate thirty years of European construction. The picture painted is a sombre one: between a surge in the extreme right, Brexit, temptation towards illiberal democracy and tensions with Russia. It almost seems that, on a geopolitical level, the Cold War is back with different kinds of walls.

However, there was an unexpected surge in participation in the last European elections, demonstrating voters’ real interest in European issues. Though Eurosceptics are still making progress, particularly in France, their rhetoric has become much milder in this respect. The Front National (National Front party) called for “Frexit”; the Rassemblement national (National Rally party - the new iteration of the Front national) is currently promoting a “Europe of Nations”. Even the Eurosceptic parties must have a clear vision for Europe if they want to get electoral results.

Despite the negative picture painted by the press, French people have more knowledge, more understanding and more interest in their European neighbours today than back in 1989.

Cecilio Pedro Secunza Schott from Mexico

The last year of “the eighties”, which had been a period of great technological, musical and of course social transformations, not only meant the fall of the Berlin Wall, but also the beginning of the end of the Cold War.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Mexico was no outsider to this political confrontation between the Western and Eastern Blocs. It had joined forces with the capitalist countries led by the U.S. by signing the Rio Treaty, a mutual defence pact. In practice, Mexico maintained a rather neutral position, maintaining unofficial relations with some socialist and non-aligned countries.

The wall also reached Mexico by means of the cinema, notably through the Mexican-Spanish film “The Boy and the Ball and the Hole in the Wall” (1965) by Mexican director Ismael Rodríguez. It portrayed a fictional episode of daily life in divided Berlin: Dieter, a five-year-old boy living on the western side of the city, accidentally throws his ball to the eastern side across the wall. The ball is recovered by Marta, a girl living in west Berlin, who refuses to return it. From this moment, both children establish a friendship through a hole they dig into the wall, which sometimes becomes protagonist of this story.

Thirty years after this particular wall fell, we have a glimpse of a new “wall of shame” on the border of Mexico and the United States: the construction of a physical barrier of great proportions. it was one of the main campaign proposals of the current American president to - in his own words - stop the flow of undocumented migrants from Mexico. “Build that wall!” can be heard at his political rallies. In stark contrast, the famous phrase “Knock down this wall” was pronounced by Ronald Reagan to demand the end of the wall in Berlin.

Thomas Cassar Ruggier from Malta

Many Maltese people feared that the fall of the Berlin Wall would lead to major war. Back then, the Maltese were fixated on neutrality, having been independent for only 25 years from the British. For Malta, going from its historical function of a military base to a neutral country was a big step. The Maltese hoped that neutrality would guarantee them independence, given that the island had been occupied by foreign powers for millennia. Therefore, confronted with the fall of the wall, the possibility of war shocked the Maltese.

What materialised instead was the end of the Cold War. The declaration was made on Maltese soil when the US and the USSR met for a summit there in December 1989. For a moment the summit heightened political tension in Malta: for the Maltese Labour Party, which was in opposition, saw the location of the summit as a move by the governing Nationalist Party as an attempt to make Malta part of NATO, thus taking away its neutrality.

In 2019, the situation is different when it comes to internal politics. The question of whether Malta is the “best country in Europe” (according to the current government) or a “functioning dictatorship” (according to the opposition) divides the Maltese. Another cause for debate among is the migration situation in the Mediterranean. The situation outside Maltese waters has made people nervous, but Malta will not see the far right in parliament. Political loyalty for the two established parties is a mainstay of Maltese society and so far, the electoral system has prevented the far right from entering parliament. However, a potential move towards the right within the structure of the two established parties is a possibility. Just like 1989, 2019 is an interesting time for the Maltese.

Arnisa Halili about Kosovo

The television pictures of the fall of the Wall still move the world today. In a conversation with my uncle, who was 37 years old at the time and living in former Yugoslavia (today the Republic of Kosovo), I wanted to find out how he experienced the fall of the Berlin Wall as a Kosovo Albanian.

He found out about the groundbreaking news on television. He describes the situation as a moment of change and hope after almost 29 years of separation of a people into two states. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the unification of the two German countries of course also had an effect on the former Republic of Yugoslavia. My uncle was personally very moved because the Albanians in the Balkans were divided just as arbitrarily. New political winds were blowing in the Eastern bloc, and the democratic movement gained ground in almost all its states. Here in Kosovo, too, they suddenly saw an opportunity to achieve their aspirations for freedom and democracy.

Niclas Hüttemann about Italy

The histories of Germany and Italy have always moved in lockstep. Rising as nations less than a decade apart, they succumbed to authoritarianism and were brothers in arms sixty years later.

From there on after, the similarities between Italy and Germany were mostly reserved to historic ties. It took the eastern GDR more than 40 years to create a political incident that would lead to Berlin and Rome to become closer once more.

Following a question from an Italian journalist, an official of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany Günter Schabowski mistakenly cast considerable doubt on the obstacles to reunification when he improvised an answer. As a result, crowds gathered at the wall.

When Italians huddled around the television to listen to the broadcast on the events of the 9th November in Germany, they did not know that just three days later they would hear the news reporter tell them about the proclaimed dissolution of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). This was a big shock to Italy – the PCI was the opposition party, the largest communist party in the western hemisphere, and was oftentimes within reach of seizing power from the Christian Democrats.

On 12th November, the “svolta”, or “Wende” or “turning point”, of Bologna took place. The PCI accepted the winds of change under its leader Achille Occhetto. Now, 30 years after Occhetto and Schabowski’s press conferences, both countries are yet again united – in talks on whether the Wende brought East and West together and if the svolta actually led to the creation of a stable and strong successor to the PCI.

Magdalena Janžić about Croatia

By the end of the 1980s, my parents tell me, it was obvious that the end of the socialist era was near. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ) faced seemingly unsolvable internal conflicts between the member states. On 9th November 1989, my parents were students working in Switzerland. Every Swiss TV channel that day showed a mass of people overcoming a concrete wall dividing Berlin. For them, and for others who had the opportunity to witness the fall from the perspective of the Western media, the crushed wall strengthened the already strong will to take steps towards democracy. However, Yugoslavia was never confined behind the Iron Curtain, and the national political turbulence that year overshadowed the importance of the event.

From today’s perspective, the events in both countries, even if not interdependently, shaped the map of opened and democratic Europe. Some years after the break-up of the SFRJ, the newly established Republic of Croatia had a new agenda – joining the European Union – and we were welcomed in 2013. As one of many Croatian students in Germany (furthermore, former Eastern Germany), I now consider the collapse of the Berlin wall not only as a bridge of German, but European unification. Thus, the value that 9th-10th November 1989 represents should be remembered and appreciated. We would do well to observe that the walls impeding free movement of people do not last.

Guillermo Íñiguez from Spain

In 1989, Spain was a young democracy: its Constitution was eleven years old, and it was only eight years since the country had survived its last military coup. Yet Franco’s death, followed by the victory of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party in 1982, had opened the floodgates of profound political, economic and social transformation.

A lot has happened in the past 30 years. The ultra-nationalistic terrorist group ETA, which killed over 800 people, was defeated by a peaceful revulsion. The early noughties saw an expansion of civil liberties and social rights, with Spain becoming the world’s third country to legalise gay marriage. A brutal financial crisis and its subsequent austerity, which immensely strained the country’s social fabric, triggered not xenophobic nationalism, but a wave of indignados which called for a fairer, more democratic society. As for the past years, its annual feminist demonstrations have earned worldwide admiration. Despite the temporary setbacks, contemporary Spain – a product of its democracy, of its liberal constitution and of its tolerant society – has consistently, if gradually, progressed and matured.

Yet against that background, 2019 is a year of uncertainty. Thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, an increasingly polarised society is once again being tested by nationalism: by a far right which unashamedly longs for a Francoist past and by a Catalan secessionist movement which, claiming to represent the people, has held itself to be above the rule of law. For the first time in the country’s modern history, echoes of Euroscepticism, undertones of Spain First, can be heard in the political arena.

If the fall of the Berlin Wall can teach us anything, it is that the goal ahead can only be more freedom, more pluralism and more democracy. That we cannot take our political rights for granted. That the best way to fight the far right and to defeat nationalism is through a united Europe. And that the time for that united Europe is now. On the eve of Spain’s most important election for a generation, and at a time where our continent is at a crossroads, we cannot afford to forget Europe’s history.

Gytis Nakvosas from Lithuania

The fall of the Berlin Wall was the main event that flagged 1989 as one of the most transformative years in the history of Europe. Before the famous evening of 9th November in Berlin, almost every socialist regime was already under immense pressure from civil society to end oppressiveness and backwardness of their countries and to begin a new era of freedom, honour and opportunities. This rapid change had already started to menace the stability of the Soviet Union itself. People in the Baltic republics were striving to achieve not only democratic rights, but to reclaim the sovereignty that was taken away by Stalin in 1940. On 23rd August 1989, the biggest peaceful demonstration, known as the Baltic Way, connected people from the three nations in a giant hand-to-hand chain. It showed unequivocally that the will to achieve independence from Soviet Union was irrepressible.

At the time when the Wessies were celebrating the fall of the wall with the Ossies, Lithuanians also had many reasons to be in emotional upheaval. Successful mass demonstrations that drew hundreds of thousands of people had put enormous faith in the citizens’ hearts. Lithuanians were actively following the rapid changes in the Central European countries, and the solidarity with the neighbouring nations was immense. The telegram messages with the news from Berlin brought a sense of freedom and bravery. After witnessing the peaceful fall of the wall in Berlin, Lithuanians already knew that the regime could no longer use any violent means to resist the will of the people. With the Iron Curtain finally broken, it was a sign that Moscow was willing to accept the change. Since the Berlin Wall was no longer dividing the free parts of Europe from the oppressed, it was obvious to our nation that a new dawn for Lithuania had arrived.

On the occasion of the thirty year anniversary of 9th November 1989, Laura Mercier, Louise Guillot and Agathe Ramade from our French sister publication Le Taurillon recorded a podcast in French:

Follow the comments: |

|