According to the Commission’s data, since 1995 – when the Schengen Treaty entered into force – border closures – which suspended the agreement – had occurred 116 times prior to the European pandemic outbreak, last March. Of course, the treaty foresees the possibility of temporary suspensions due to extraordinary circumstances, such as when terrorist attacks and other, similar threats emerge.

The first phase of the health emergency saw an unprecedented reality: almost all EU Member States considered and/or enacted unilateral decisions to close the national frontier. Responding to these decisions, President Von der Leyen’s commission acted promptly; by mid-March, they published guidelines on how to manage national borders without endangering the single market. Stressing the fundamental need for unity in times of crisis, the document shunned discriminatory measures which would result in a deterioration of bilateral relations. Out of the 26 states part of the Schengen space, 18 countries suspended Schengen and closed their borders at some point in the period between March and June 2020.

Although the pandemic’s first wave passed, issues of border controls and international movement continued to trouble heads of states. For starters, they faced numerous problems in establishing health safety criteria in order to reopen borders.

Undoubtedly, diplomatic equilibrium is sensitive to change, and international relations are extremely delicate. A good example is Germany: where the Belgian border remained open, despite the latter having one of the worst COVID-19 death rates in the world, and yet restrictions were placed on individuals coming from Italy or Spain. Since the German government had not put forward explicit and precise criteria, these Southern-European countries felt slighted and accused the Chancellor Merkel of discrimination. Eventually however, the policy was clarified. In fact, the summer period saw all Member States loosen their restrictions. However, similar episodes since the second wave hit Europe this fall have continued to fuel tensions.

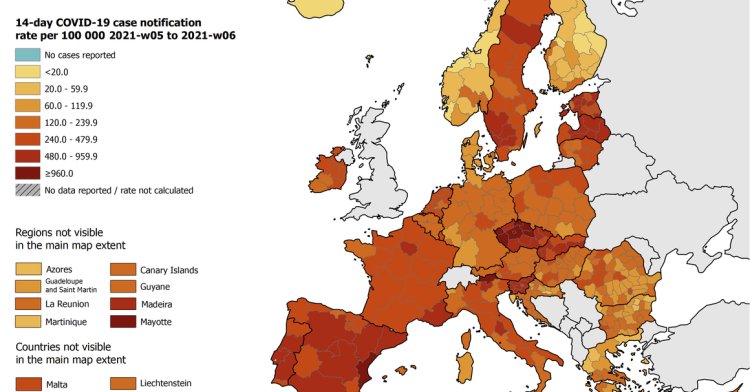

As Europe experienced this second wave and the COVID-19 cases began to rise again, the necessity of quick and ad hoc measures became evident. After having witnessed the unregulated fashion in which Member States reinstated border controls, the EU’s General Affairs Council put out a non-binding recommendation to promote a coordinated effort and safeguard free movement within the Schengen area. The Commission put forward a proposal complementing the guidelines, in which Member States agreed to design a colour-based system to clarify and centralize pandemic data. Every state provides their COVID-19 case notification rate per 100,000 people from the last 14 days. This information is received and recorded by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), which is also in charge of presenting the whole EU’s overview report.

Although the EU institutions deployed various efforts to try and manage their internal borders, policy decisions over national border closures are, and have always been, the exclusive competence of the state itself. Thus, it remains unclear if there is any chance of further cooperation at the EU level, and if future initiatives would actually lead to optimal outcomes.

What about the external borders?

It is important not to get lost in the Schengen area’s various debates and difficulties and ignore the tragedies and human rights violations occurring at the EU’s doorstep. These horrors must be addressed urgently.

Only five months ago, in September, the world witnessed the tragic fire that destroyed the refugee camp in Lesbo – a facility designed to host less than 3,000 people –, leaving over 13,000 refugees with nothing but the clothes on their backs and no place to go. According to InfoMigrants, around three-quarters of the displaced population come from Afghanistan, but individuals from over 70 countries lived inside the camp. The origin of the fire has not been confirmed. Still, the hypothesis that this was not an accident is highly plausible: the UNHCR and other organisations have repeatedly warned of the rising tensions between refugees and locals, in addition to the worryingly overcrowded site. Unfortunately, the Moria camp case was not an isolated one.

Currently, in Lipa, Bosnia and Herzegovina, a few thousands of refugees live without a shelter after a fire broke out last December and burned down all the camp’s tents. The facility’s construction was funded by the EU last April, when hundreds of people – mostly from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan – settled there hoping to soon enter the EU via Croatia. On the one hand, the EU, via its Commissioner for Crisis Management Janez Lenarcic, blames Sarajevo for the inadequate resources implemented to grant protection to the displaced; they claim that the Bosnian government prioritised the local citizens’ will not to help or host refugees, making it explicit that they are not welcome there. On the other, the EU is accused of delegating the problematic task of managing refugees inflows to a less democratic third state, exposing the refugees to a wide range of risks; these accusations are akin to those regarding the 2016 EU-Turkey agreement.

Whichever side the blame lies upon, at the end of the day, the suffering party is once again the refugees. They are currently dying on the EU’s front porch as temperatures fall below zero daily, to minus 10 degrees. The horrible reality is just one more example of how crucial border management is, and how the debate about the matter is deeply intertwined with the Common European Asylum System and other policy areas.

Follow the comments: |

|